Note: Check out my original 2009 review to see how much of a better writer I am now

The dirty little secret of the Fast and Furious series is that they were never really about the cars they so proudly displayed. Writer Gary Scott Thompson used the Vibe Magazine article “Racer X” as an inspiration for the first installment, but the series has proven itself to be a strange and ever-changing beast since entering the pop culture landscape 14 years ago. And then there’s the popular, rather true notion that the original movie is basically just Point Break with cars instead of surfboards, and we never talk about Point Break as a surfing movie. The Fast movies are an often lost and yet bizarrely coherent collection of pieces that have adapted to extenuating circumstances over time into something bigger and altogether more interesting than originally envisioned.

However, to understand the context of its zigzagging

evolution we need to return to the beginning. The characters of The Fast and the Furious live apart from

the rest of us with their unique world that’s powered by magically ready-made

rolls of cash, a little elbow grease, and a lot of attitude. The movie presents

a clear distinction between the “normal” world and the nightlife racing culture

as the sun sets and the flashy neon cars light up the streets. Director Rob

Cohen lovingly pans his camera across these cars with as much fetishistic glee

as he does the scantily clad women that cling to the drivers like rock band

groupies. Cohen and Thompson create this insular microcosm of people that all

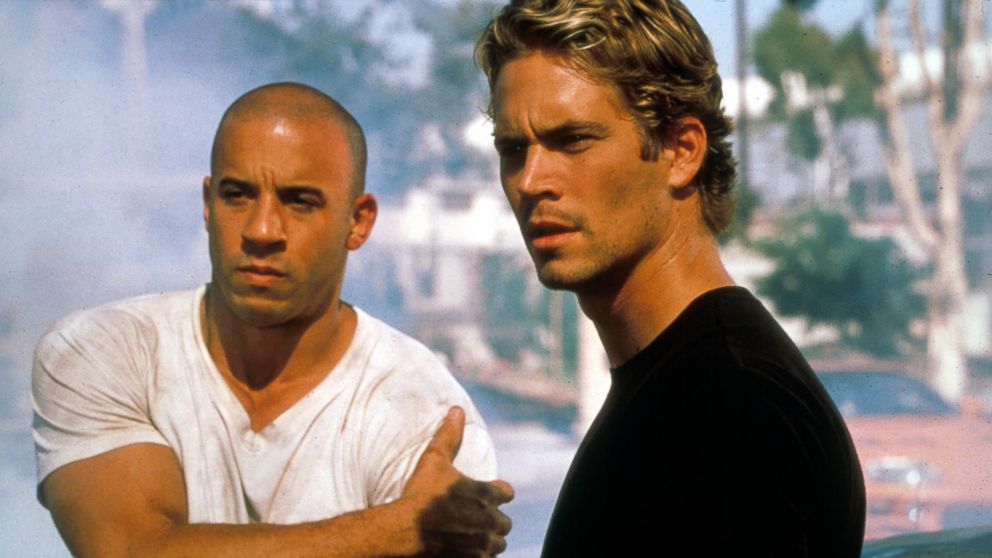

know each other and the code of respect that defines them, so when Paul

Walker’s Brian O’Connor presses his way into this circle he immediately stands

out like bleached-blonde sore thumb.

Walker’s severe stiffness as an actor almost works for the

character; sometimes it’s hard to tell in the early scenes whether Walker is

just trying to pull off a convincing line delivery or if the actor is playing

this up to emphasize the undercover cop’s weariness. Walker’s lack of screen

presence, intentional or not, is put into perspective every time he shares a

scene with Vin Diesel’s Dominic Toretto. Before we even get to know Dom, Cohen

and Thompson lay the bricks for his legend status in the racing community.

Cohen stages his introduction in such a way that we already understand the type

of person he is before Diesel opens his mouth. With his back turned to the

camera and two crossed shotguns adorning the office wall, Dom is immediately

established as the outlaw figure who only enters trouble when absolutely

necessary.

In Diesel’s hands Dom is the ideal image of macho bravado

without the toxic impulsiveness that undoes many of the other characters in

this society, including those in his own crew. Even as the Fast movies found their voice late in life, their baritone lead

actor never quite recaptured the same level of charisma he displayed here. The

hyper-macho attitude extends to everyone else in the movie, with every guy

trying to one-up each other in races and insults. So pervasive is the movie’s

manly nature that one of its few prominent females, Michelle Rodriguez’s Letty,

is so masculine that she takes the phrase “just one of the guys” to another

level.

The only sensible way for these people to vent themselves is

through the thrill of underground street racing, a life so in-tuned to their

desires that they might be able to describe the accessories of their cars

faster than Cohen can montage them. But Cohen has a few tools of his own; his

computer-assisted journeys into the car engines have become a trademark element

of the series. A character’s press of the NOS button is more than just a little

boost, it’s an intricate mini roller coaster that gets to the literal heart of

these speed machines and provides the movie’s audience with an adrenaline shot

of their own. Cohen pushes the effects to such a degree in the first drag race

that the cars feel like they’re gliding more on pixels than pavement as he

relies too much on green screen effects when real driving would have worked to

better effect.

This is certainly true with the botched truck robbery that

comes right as everything starts falling to pieces for both the characters and

the increasingly haphazard plot momentum. When looking at the larger set pieces

to follow in the sequels, this sequence is rather stripped back in comparison,

and to its advantage. Dom, against his better judgment, tries to save resident

asshole crewmate Vince from the shotgun-wielding driver, whose faceless

presence gives him an otherworldly quality, recalling the sinister and also

unseen villain of Steven Spielberg’s classic Duel. The entire sequence is accomplished with nary a trace of

digital trickery, allowing the tension to build naturally through a series of

close-calls, daring maneuvers, and Dom’s refusal to let his friend go.

This drives at the heart of what this tight knit group of

people is all about, which is the binding force of family. For all it’s races

and clashes, of which there’s surprisingly little of for an action movie, The Fast and the Furious is much more

concerned with its bromantic bonds and attitude than it is about getting the

adrenaline pumping, which works both for and against itself. Like any outlaws,

Dom and his crew live by a code; it’s just that this code is often expressed

through the simple pleasures of a Corona and some barbeque with mates. The outlandish world of street racing

is made human, even as it retains its ridiculous nature with earnestly acted

nonsensical dialogue such as, “I live my life a quarter mile at a time.” Try as

it might, words and convincing emotion aren’t the movie’s strong suits.

This presents a problem later on when the drama feels like

it should be hitting a peak and yet stalls out repeatedly in the third act. The

plot continuously pivots around its multiple threads and never manages to bring

them together in a cohesive fashion, leaving the disjointed climax to fizzle

out before it can generate real excitement. The final drag race between Brian

and Dom feels like a forced attempt to provide closure, especially when the

impending threat of Brian’s LAPD superiors turns out to be a total non-starter.

The perfect analogy for The Fast and the

Furious is Brian’s first street race experience: he has the right tools and

just enough bluster to carry himself through, but he sputters out wildly before

hitting the finish line, leaving a trail of smoke and little else to show for

it.

No comments:

Post a Comment