The Fast and the Furious: Tokyo Drift (2006)

Tokyo Drift finds

itself in a precarious position in the Fast

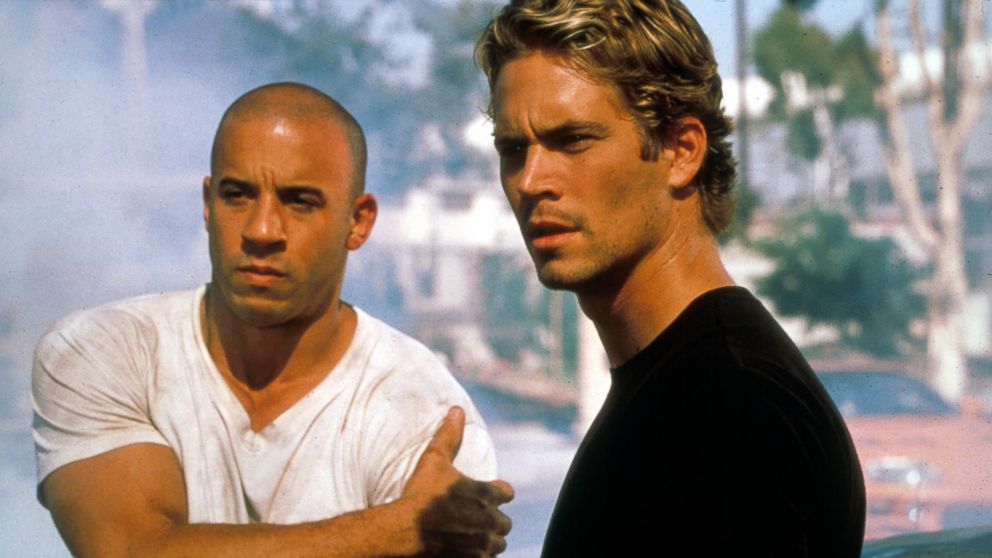

and Furious movie series. When Paul Walker declined to return, the

production wiped the slate clean with an entirely new cast and crew that almost

completely ignored the previous two installments. This paved the way for

director Justin Lin and writer Chris Morgan’s partnership to bend the movies to

their creative wills for four straight entries. It’s also a bridge film of

sorts between the grittier action movie approach of the later Fast films and the earlier, more

colorful racing-focused phase of the series. Tokyo Drift represents both the end times (almost literally,

considering its low box office) and the beginning of a new era, the first

indication being that Lin and Morgan crafted by far the best movie in the

series yet at that point in time.

Tokyo Drift is

essentially the Halloween 3 of Fast and Furious movies: shunned by fans

at the time of its release for not featuring the old characters, and then later

accepted as a cult favorite. It takes the same combination of oversized egos

and machismo and transplants them to a new setting where they feel right at

home: high school. If The Fast and the

Furious was Point Break and 2 Fast 2 Furious was Miami Vice, then Tokyo Drift is the Karate Kid

of the series. Southern boy protagonist Sean Boswell (Lucas Black) is an

outsider even in his hometown, and with a 1971 Monte Carlo as his early car of

choice the movie establishes from the start that he’s a gear hound amongst a

bunch of wannabe chest-pumpers.

But the movie serves as a subtle subversion of the series’

sense of bravado by having Sean mess up…a lot. Even when he beats the asshole

jock in the opening he still ends up wrecking his car, and up until late in the

game Sean’s ego is consistently brought down notches once he’s shipped off to

Tokyo to live with his father and to quit racing. Of course he doesn’t quit,

because there needs to be a movie, and he ends up losing badly to local racing

celebrity “D.K.” (Drift King). Despite this, he catches the eye of racer Han

Seoul-Oh (just roll with it). Han is an anomaly in this crowd; he doesn’t

engage with the boasting attitude that permeates this mini-society, often

standing to the side eating his snacks while everyone else talks their heads

off.

Han is the true standout of Tokyo Drift, and much of this can be attributed to Sung Kang’s

nonchalantly cool performance. He doesn’t need to say much because he knows

that he can walk the walk while everyone else is too busy throwing horribly written

insults at each other (the dialogue may debatably be the worst in the series,

which is quite an accomplishment), and his Zen-master training helps Sean

become a better racer. With all-due respect to the late Paul Walker, Lucas

Black is a much more charismatic lead for these movies, capturing the cowboy

fun and excitement of shifting into high gear and barreling through the

neon-lit streets of Tokyo.

What pushes this particular Fast and Furious over the edge as one of the best in the series is

the sense that Lin and Morgan are having fun with the material too. This is

immediately apparent in the action sequences, each of which is different and

wilder than the last and display a greater sense of rhythm than any seen in the

previous movies. Lin’s set pieces crackle with reckless energy, particularly

during an escape from D.K.’s goons and the final race along the winding

mountainside roads. The addition of drifting into the mix is mostly just window

dressing, though it allows for much more exciting scenarios than simple drag

races. Lin’s more straightforward style is less reliant on gimmicky tricks to

translate the adrenaline rush to his audience, letting the frenzied editing and

camera do the work on their own.

The director understands how to project the thrill of racing

better than his predecessors did, and it’s not hard to see why his and Morgan’s

partnership on this series lasted for four movies straight. They understand

that driving is in the blood of these characters; they live and breathe it.

Sean’s romance with local schoolgirl Neela is best expressed not with words but

when she takes him for a graceful ride along the countryside. Due to this and

other factors, Tokyo Drift is

arguably the only movie of the bunch that, at its heart, is truly about racing.

Even the first and second movies owe themselves more to their crime genre

influences than gear head classics such as Gone

in 60 Seconds (1974), and when Sean finally owns up to his poor decisions

to D.K.’s gangster father (martial artist Sonny Chiba), their agreement boils down

to one final race to settle the rivalry.

The characters are played straight but the tone of their

adventure is done with a subtle nudge and wink (Bow Wow’s annoying sidekick

Twinkie literally winks at the camera when he enters an elevator full of women).

The backdrop of Tokyo provides a colorful playground for the characters to roam

in, and Lin relishes in the cartoonish little details of the racing world like

Twinkie’s tricked-out Incredible Hulk car. The term “car porn” has often been

applied to these movies and that has never been more true than here, basking in

the sleek edges of international sports cars while admiring the raw power of

American muscle. Tokyo Drift is about

the bridging of cultures and worlds across the sea, all of which is given a

nice bowtie when Vin Diesel’s Dominic Toretto shows up at the end to race Sean,

a nice acknowledgement that the movie is not just The Fast and the Furious in name only. It would be a shame to toss

the movie aside because of its hard-swerve into a new direction for the

franchise, one that would set the course for the insane heights to come.